The West Coast Libertarian Foundation website has been offline for a while as it had been hacked. It is now on a more secure server and hopefully won’t be subject to further attacks. It had been quite a while since anyone had posted a new article here in any event, so to relaunch it I am posting my most recent article from my personal blog, The Jolly Libertarian.

On another note I have started recreating the wealth of newsletters from the early days of the libertarian movement in Vancouver and will keep adding to it over time. It is a rich historical record of the movement and should be preserved as such.

Book Review: Sister Revolutions by Susan Dunn

reviewed by Marco den Ouden

Sister Revolutions by Susan Dunn is an intriguing read. Subtitled French Lightning, American Light, it compares the American Revolution and the French Revolution. It was recommended to me by a conservative friend who argues that the American Revolution was a conservative revolution, not a Lockean liberal one as argued by American political scientist Louis Hartz in his book The Founding of New Societies.

Sister Revolutions by Susan Dunn is an intriguing read. Subtitled French Lightning, American Light, it compares the American Revolution and the French Revolution. It was recommended to me by a conservative friend who argues that the American Revolution was a conservative revolution, not a Lockean liberal one as argued by American political scientist Louis Hartz in his book The Founding of New Societies.

The subtitle comes from American Founding Father Gouverneur Morris. Morris was one of the few to speak out against slavery at the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention. He lambasted the idea that the Southern states should have their representation increased by counting every slave as 3/5 of a person even though they were not recognized as free men. James Madison paraphrased him thus:

The admission of slaves into the Representation when fairly explained comes to this: that the inhabitant of Georgia and S. C. who goes to the Coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections & damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a Govt. instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than the Citizen of Pa. or N. Jersey who views with a laudable horror, so nefarious a practice.

Morris is also noted as the author of the Preamble to the Constitution:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Morris was charmed by French society, but as Dunn puts it, “he was unimpressed by the French ‘Leaders of Liberty’ who seemed to wish to annihilate much that was precious in France.” He viewed them as radicals with no experience in government. In his Diary of the French Revolution (he was appointed America’s minister to France in 1792) he wrote that the French “have taken Genius instead of Reason for their Guide, adopted Experiment instead of Experience, and wander in the Dark because they prefer Lightning to Light.” (Quoted in Dunn page 39)

Dunn’s thesis is that there were fundamental differences between the two revolutions. The American revolutionaries were practical men with experience in government. They were not wild-eyed visionaries off to remake society holus bolus. The French, however, were ideologues, philosophes with an abstract vision for a perfect society. They wanted to tear out the old regime by its roots and replace it completely. They distorted a lofty vision into justification for the bloodthirsty excesses of the Jacobins and the Reign of Terror.

The Americans wanted to have the same rights as any Englishman, rights they saw usurped. They fought to regain what they had lost. The French were out to overthrow what they saw as an unjust and corrupt system.

Ironically, the French king Louis XVI sympathized with the American revolutionaries and bankrupted the French treasury supporting the American cause. As Dunn puts it, “Louis XVI could not imagine that within a decade his generosity would egregiously worsen the economic crisis in France, subvert all traditional values, destabilize the monarchy, and put his own life in jeopardy.” (6)

The help of the French in 1780 with the Marquis de Lafayette at their helm proved to be “the turning point of the war.” The decisive battle of the American Revolution, the battle of Yorktown, had more Frenchmen than Americans fighting against the British. Without French help the war could have been lost.

Dunn starts off the book by using Lafayette as a connecting thread between the two. She points out that

the sister revolutions of the eighteenth century hold invaluable lessons for our contemporary democracies. Not only do they illuminate our political assumptions, beliefs, and ideas, but they also help us to take the temperature of our political cultures, to diagnose our political ills, and to prescribe remedies for them. (25)

Dunn argues that the two revolutions took different courses because each was based on a different idea, a different ethos. While both were ostensibly based on the idea of the rights of man, the interpretations of that lofty goal differed.

The American was motivated by a philosophy of diversity that focused on protecting individual rights. It recognized that men varied in their interests and ambitions, in their tastes and goals. Anticipating Isaiah Berlin’s value pluralism, they fought to protect the rights of individuals and minorities.

The American Revolution was led by men experienced in politics. All the principals had or were serving in various state legislatures. They knew the value of and necessity for negotiation and compromise.

The French, on the other hand, were visionaries and dreamers without any practical experience. And while the Americans were concerned with diversity and the rights of minorities, the French believed in unity. They saw France as a united nation, united in its ideals. United in its vision.

Dunn characterizes this difference as one of evolution versus revolution. And while an older Thomas Jefferson, the most radical of the American revolutionaries, supported the French cause, the Declaration of Independence he penned as a younger man was tempered. It was, as Dunn puts it

a document simultaneously backward- and forward-looking, upbraiding the king for interfering with Americans’ traditional freedoms and boldly announcing a new society based on the individual’s unalienable rights. Unlike the older Jefferson who would yearn for freedom from history, the younger Jefferson anchored his Declaration in tradition and history. (51)

Americans welcomed change. They lived in a dynamic and uncharted territory. On the other hand, England was mired in stagnation. “The dread of innovation there,” Jefferson noted, ” has, I fear, palsied the spirit of improvement.” (quoted on page 52)

The Americans recognized that conflict among human beings was inevitable. The consensus reached at the 1787 Constitutional Conference was based on compromise. The American leaders “toiled six days a week on the new Constitution, hammering out compromise measures, from the problem of representation in Congress for smaller states to the issue of counting slaves in the representation of the South.” (53)

But the key element, according to Dunn, is the recognition that conflict is part of human nature. Indeed conflict ensued from the get-go after the Constitution was “agreed to and signed in Philadelphia.” Dissension between Federalists and anti-Federalists was rife. While the Federalist James Madison was troubled by these conflicts, he also welcomed them. His essay in The Federalist No. 10 promoting acceptance of the Constitution by the anti-Federalists (the Constitution still had to be ratified by the states) was focused on diversity and conflict.

Madison’s plan for American government gave free rein to citizens to act in their own self-interest, to form factions, to enter into conflict with one another, and the predictable result would be disorder and tumult. The government would make no attempt to eliminate conflict – that is, non-violent and rational contention – only to moderate it and provide channels for it. (54)

But while the Americans embraced conflict and diversity of thought, in France

the momentum of the Revolution was toward order, not tumult, towards oneness, not multiplicity. Far from accepting diversity and conflict, the French worshipped homogeneity and unanimity. Their leaders believed the salvation of the Revolution depended above all on absolute unity and solidarity of the people. According to their revolutionary agenda, three orders – nobility, clergy, and Third Estate – would become one, 25 million citizens would form one unitary people. All would sacrifice their self-interest for the common good of all; diverse opinions would yield to consensus. (55)

Madison recognized that “citizens are individuals and that as individuals they are all different.” For Madison, “the principle of diversity seemed embedded in human nature.”

Madison argued that rational people view issues in different ways because reason is essentially imperfect. “As long as the reason of man continues fallible,” he maintained, “and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed.” (55)

Dunn goes on to cite the influence of Machiavelli who wrote that tumult was “the guardian of Roman liberties.” (The Discourses)

Meanwhile the French Revolution was heavily influenced by the writings of Emmanuel Sieyès, a forty year old priest who wrote a pamphlet called What is the Third Estate? “Sieyès was Madison’s French counterpart, the artisan of revolutionary ideology.” (59)

Sieyès urged the abolition of the Estates General and the formation of one National Assembly. “The nation and the Third Estate, he insisted, were one.” The nation could do without the nobility and the clergy. He, himself, renounced his privileges as a member of the clergy and was elected to the National Assembly “as a representative of the Third Estate.” (60)

The key to Sieyès’s vision of a new France – and the concept that shaped the Revolution’s politics and became its mantra – was unity. (60)

“The nation, one and indivisible” became the rallying cry for the Revolution.

People swore oaths to it, agreed to die for it, and denounced traitors to it. The salvation of France and the success of the Revolution appeared to hinge on the indivisibility of the nation. (61)

Dunn notes the influence here of Rousseau’s theory of the General Will. “Composed of this one order, the nation would possess one single will and could therefore deliberate and legislate purposefully and effectively.” Sieyès

conceived the Third Estate not as a diverse population of heterogenous individuals each acting in his own self-interest, but rather as a homogenous mass devoted to the common good. This philosopher-politician, more comfortable with abstract ideas than with unruly human beings, envisioned all members of the Third Estate not only as equal but also as like-minded, sharing the same opinions, ideals, and revolutionary goals. Indeed, the hallmark of a citizen was the commonality he shared with other citizens. (61)

Any incidental differences were “beyond the sphere of citizenship.”

This was in direct contrast to Madison’s vision who saw “only the interests and wills of diverse citizens and factions, all competing for influence and power.”

The upshot of this was two completely different political outcomes. The Americans developed a Constitution and a government based on the idea that there would always be contentious issues and contentious factions. Thus the Constitution was devised as a system of checks and balances with countervailing powers to prevent any faction or group from attaining dominance. The Executive branch and the Legislative branch and the Judiciary were independent and separate. And the Legislative branch was further divided into the House of Representatives and the Senate, each again designed to provide countervailing powers.

Dunn notes that for Rousseau, “true freedom consists in choosing to obey the General Will.” Americans saw heterogenous individuals, each free “to act as they wished, in a variety of diverse ways, and pursue their self-interest and happiness as they conceived them.” (62)

Madison proposed “a kind of ‘negative freedom,’ freedom from constraint,” while Rousseau plumped for a positive freedom, “freedom for some higher good, for the enjoyment of a moral life as a citizen devoted to the common good.”

In Rousseau’s utopia, “the General Will has come to dominate all of society and its laws. Every citizen must submit to its infallible, unlimited authority.” (63) “What king ever ruled so absolutely,” Dunn asks sardonically.

In a famous line from The Social Contract, Rousseau writes “Whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be constrained to do so by the whole body: which means nothing else than that he shall be forced to be free.” (emphasis added)

Not surprisingly, the French Revolutionaries known as the Jacobins, once gaining power, started to root out heretics. The ones who would not submit to being “forced to be free” became fodder for the guillotine. Dunn provides some salutary quotes.

Factions, Sieyès declared, “create the most fearsome public enemies.” “No one knows better than I,” proclaimed Mirabeau, “that the salvation of everything and of every one resides in social harmony and in the annihilation of all factions.” “I abhor any kind of government,” Robespierre stated succinctly, “that includes factious men.” “We will not permit a single heterogenous body in the Republic.” pronounced the delegate Garnier. (88)

The Reign of Terror started to consume the moderate elements. The Girondins, also promoters of the cult of unity, were prosecuted for “undermining the indivisibility of the Republic.” Dunn notes that “the historian Michelet remarked that no hypocrisy colored the trial, for absolutely no attempt was made to follow legal procedure. The sole purpose of the trials, he lamented, was to murder the opposition.” (90)

The trial, Dunn suggests, was “probably the single most catastrophic blow to political pluralism.” The original Constitution of the revolutionary government had maintained the inviolability of members of the National Assembly so they all could speak freely. That protection had been revoked six months before the trial. Now the leading Girondins mounted five tumbrels to take them to the guillotine.

The rabid and blood-thirsty Marat had declared the new mantra: “Let us strike down the traitors wherever they may be.” The Jacobin St, Just proclaimed that “what constitutes a republic is the total destruction of everything that stands in opposition to it.”

“The freedom of ‘Man’ may be unambiguous,” she writes, “but the freedom of the ‘Citizen’ has many boundaries.”

The rights of the community took precedence. The emphasis that the Revolution always placed on the unity of the nation was translated into rights for the group as a unitary whole, not for autonomous, self-interested, or potentially disruptive individuals or minorities.” (152)

Rights for the French, became “irreconcilable with the expression of opposition and conflict.” She suggests it is significant that “the right to assemble peacefully” is absent from the French document. It “betray(s) the French apprehension that organized groups and factions would disrupt social order as well as the people’s unity.” (153)

The Americans “sought to protect individuals and minorities from an oppressive majority” while the French declaration “was founded on the fear that self-interested individuals and ‘particularistic’ minorities could disrupt the harmony and collective well-being of the nation.”

The Americans emphasized the individual, the French the collective. She emphasizes, though, that it was not so much the language of the declaration as “the French revolutionary belief system – the ideology of unity and the concomitant unwillingness to protect minorities” that spelled doom for the idea of rights in France.

She concludes with some reflections on problems with the American system, notably its tendency towards bureaucracy and the slow pace of change. She shares Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor’s lament that the American democratic ideal of checks and balances restricts “the formation of democratic majorities around meaningful programs that can then be carried to completion. (The Malaise of Modernity page 115)

She sees the value in the recognition of the rights of minorities but feels it hamstrings collective action. She ends up by lauding the British parliamentary system which she sees as a hybrid of the American and French approach. She sees it as protecting both the rights of individuals while recognizing the prerogative of the executive (the Cabinet and the Prime Minister’s Office) to take effective action for the common good. This is one area of the book I disagree with her on but won’t go into an elaborate discussion.

Indeed the philosopher Karl Popper in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies argues that the question of who should rule is the wrong question to ask. Rather the questions should be “How can we so organize political institutions that bad or incompetent rulers can be prevented from doing too much damage?” (page 121 of Vol. 1) This was precisely the goal of the American founders.

This leads to what Popper calls piecemeal social change, an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary approach. And this is what, ideally, the American Constitution is about.

Sister Revolutions is a brilliant little book. A joy to read and ponder on.

Other Links of Interest

There has been a lot of antagonism towards corporations. Surprisingly, not all of it from the left. I’ve come across a fair number of Facebook posts and articles from purported libertarians condemning the corporation as a creation of the state, and arguing that corporations wouldn’t exist in a true free market economy.

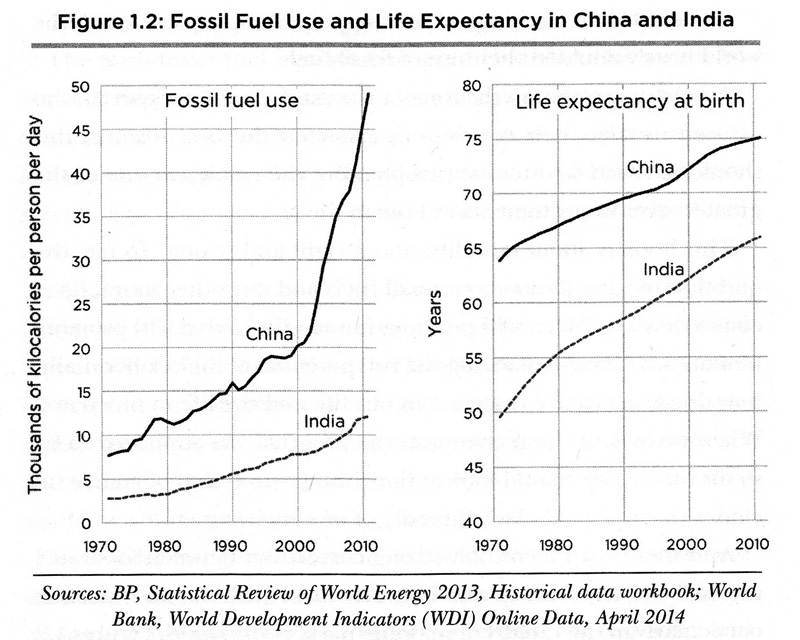

There has been a lot of antagonism towards corporations. Surprisingly, not all of it from the left. I’ve come across a fair number of Facebook posts and articles from purported libertarians condemning the corporation as a creation of the state, and arguing that corporations wouldn’t exist in a true free market economy. The alternative energy sources touted by climate change activists, namely solar and wind, are unreliable at this time, not to mention very expensive. While their use has increased dramatically, fossil fuels still provide 87 percent of the world’s energy needs. It is abundant (over 3000 years of supply available at current consumption rates) and it is cheap by comparison.

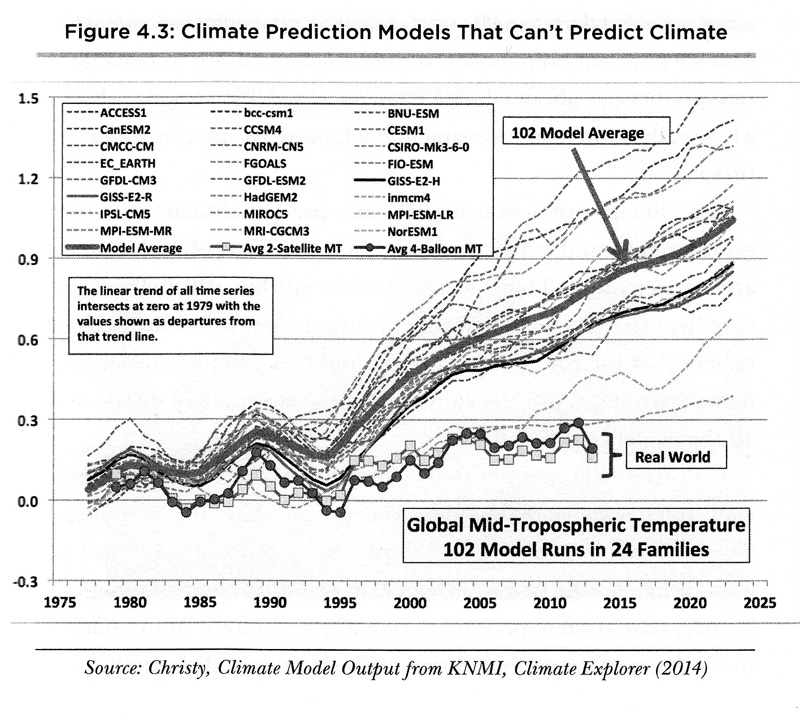

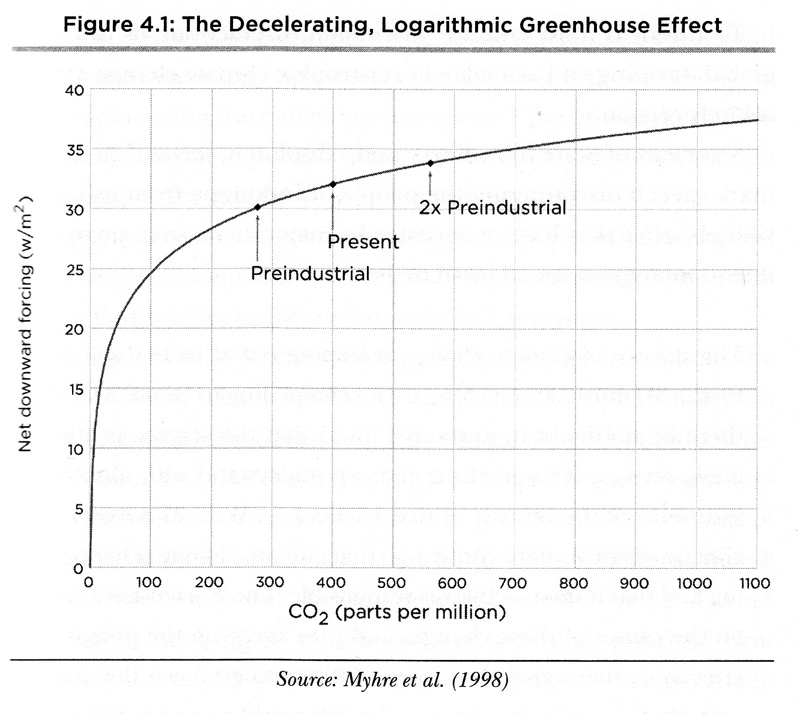

The alternative energy sources touted by climate change activists, namely solar and wind, are unreliable at this time, not to mention very expensive. While their use has increased dramatically, fossil fuels still provide 87 percent of the world’s energy needs. It is abundant (over 3000 years of supply available at current consumption rates) and it is cheap by comparison. One of the reasons for this failure, notes Epstein, is the decelerating, logarithmic greenhouse effect. Laboratory studies on the warming effect of CO2 in the atmosphere show that above a certain level (a level we have already reached) the warming effect decelerates rapidly. Each additional unit of carbon has a marginal effect at this point. He says that the doomsday scenarios are based on a speculative theory that the greenhouse effect is amplified by other effects. Their models are based on this theory and that is why they have failed.

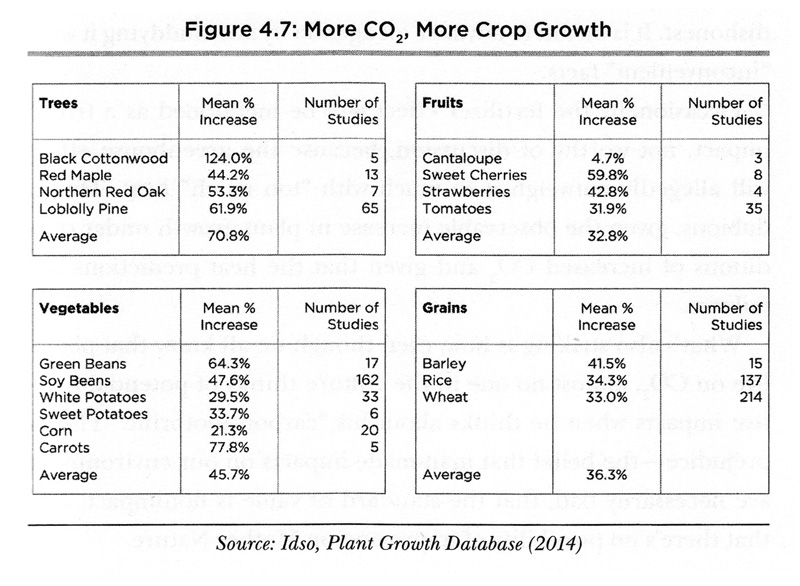

One of the reasons for this failure, notes Epstein, is the decelerating, logarithmic greenhouse effect. Laboratory studies on the warming effect of CO2 in the atmosphere show that above a certain level (a level we have already reached) the warming effect decelerates rapidly. Each additional unit of carbon has a marginal effect at this point. He says that the doomsday scenarios are based on a speculative theory that the greenhouse effect is amplified by other effects. Their models are based on this theory and that is why they have failed. Epstein avers that climate change activists work from a standard of non-impact. They work from the assumption that any impact on the climate from mankind must have negative consequences But this is a false assumption, he argues. Why can change in climate not be a positive?

Epstein avers that climate change activists work from a standard of non-impact. They work from the assumption that any impact on the climate from mankind must have negative consequences But this is a false assumption, he argues. Why can change in climate not be a positive? And what about the much ballyhooed claim that 97 percent of climate scientists agree that there is global warming and that human beings are the main cause? The claim was made by John Cook who runs the website SkepticalScience.com. Cook said he studied the research papers extensively and came to that conclusion. But Epstein says that only 1.6 percent of those studies explicitly stated that humans caused at least 50 percent of climate change. The vast majority were unquantified and Cook took it upon himself to create a category called “explicit endorsement without quantification”. The 97 percent claim is a misrepresentation of the facts avers Epstein.

And what about the much ballyhooed claim that 97 percent of climate scientists agree that there is global warming and that human beings are the main cause? The claim was made by John Cook who runs the website SkepticalScience.com. Cook said he studied the research papers extensively and came to that conclusion. But Epstein says that only 1.6 percent of those studies explicitly stated that humans caused at least 50 percent of climate change. The vast majority were unquantified and Cook took it upon himself to create a category called “explicit endorsement without quantification”. The 97 percent claim is a misrepresentation of the facts avers Epstein. Just saw the new movie Kingsman: The Secret Service

Just saw the new movie Kingsman: The Secret Service